Sources:

A Night To Remember by Walter Lord (book)

On A Sea of Glass by Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton & Bill Wormstedt

Titanic: Death of a Dream, The Legend Lives On (documentaries)

Wikipedia

Various survivor testimonies

In 1898 American writer Morgan Robertson brought out a book called Futility, which detailed the plight of an Atlantic liner full of rich & complacent people. The ship weighed 66,000 tons displacement (a measurement based on the number of long tons of water its hull can displace), was 800 feet (244 metres) long, had a top speed of 24-25 knots (28mph), a capacity of around 3,000 people, lifeboats for just a fraction of these and was labelled ‘unsinkable’. On a cold April night, it struck an iceberg and sank, killing almost everyone on board. An alternative title of the book was ‘The Wreck of The Titan’, which included the name of the fictional vessel.

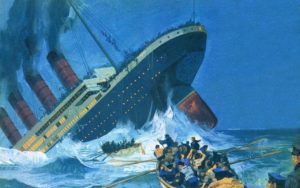

The subject of this piece was a real steamer, a beautiful, wonderful and incredibly elaborate ship. which had a weight of 46,328 tonnes (66,000 tons displacement), was 882.5 feet (269 metres, equivalent to 4 city blocks) long, 92.5 feet (28.1 metres) wide and had a height measured from waterline to boat deck of 60.5 feet (18.4 metres, equivalent to 11 storeys). Her name, known to millions over whom she has cast a spell since she was built, was R.M.S. Titanic, and her legacy has continued to grow over time. This is a remarkable story and would have been compelling if it had been made up. Instead, it really happened, and it’s a story that appears to encompass an entire sweep of people, actions and consequences. It could be that we are drawn to tragedies in a macabre way that we’d rather not admit to ourselves and others, or it could be that we really just want to learn more about the mysteries of life and ourselves and wonder how we would react if such a thing happened to us.

She was the largest ship in the world, designed to be the epitome of style, luxury and safety. However, she would suffer a disaster that would shatter the faith of an age. In the words of survivor Jack Thayer, commenting on the time before it happened, ‘there was peace and the world had an even tenor to its way’. Nothing since Napoleon had really shaken the confidence of this era in time, and the Industrial Revolution, leaving aside its darker sides of squalid conditions and manipulation of workers, had transformed productivity beyond recognition. This was of course in large part thanks to machines and technology, but it was man (plus woman and children!) who was operating and in control of it. The wars that had plagued Europe for centuries had ceased, and a new century had recently been born. This century would of course bring 2 World Wars, the killing of hundreds of millions by governments and dreadfully misplaced ideologies, and incredible progress in the technological manufacture of destructive weapons. It is often said that the Whitechapel Murders, carried out by the still-unknown killer Jack the Ripper, gave birth to the 20th century even though they happened 12 years prior to 1900. The Titanic’s sinking also served to wake people up with a start and cause them to rub their eyes and reconsider their sleepy complacency. Jack Thayer’s quote ends with the musing that ‘to my mind, the world of today awoke on April 15th 1912’

To help the understanding of this story, here are a few basic boating terms which need to be known:

(all the following directions naturally refer to both boats and ships)

Bow= the front of the ship

Stern= the back of the ship

Port= the left side of the ship (looking from the back)

Starboard= the right side of the ship (from the back)

Forward= moving towards the front of the ship

Aft= moving towards the back of the ship

Ahead= when the ship is moving in a forwards direction

Astern= when the ship is moving in a reverse direction

The Atlantic Ocean, which traditionally divides the Old and New Worlds, has a mind-boggling total area of 41,100,000 square miles, which converts to around 20% of the Earth’s total surface and 29% of its water surface. Even so, for those who are interested, it is still a long way behind the Pacific Ocean’s unfathomable area of 63,800,000 sqm, which consumes 33%/46% of the total Earth/water surface. Although it is nigh on impossible to calculate the amount of different species living in the ocean, the figure has been said to be over 220,000. It is no surprise then that humans have always had a fascination for the sea, and the smarter among them have also treated it with a due reverence and an unwillingness to go too close to its heart. The rugged Northern part of the Atlantic, divided from the South Atlantic by the wind-driven Equatorial Counter Current, eclipses all but the 2 polar oceans in its low temperatures. It is a harsh and jealous sovereign, demanding of man’s respect and vengeful against his arrogance. 400 miles off the grand banks of Newfoundland, well over 2 miles below a restless surface, this ocean holds fast to its most famous prisoner, once one of humankind’s crowning achievements. From the world’s wealthiest industrialists to the humblest immigrants, Titanic’s passengers, despite containing a disparaging range of social classes, mostly had one thing in common- confidence in the ship and a world that was ‘always getting better’, quite a rational argument when you think of what ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’ are supposed to be. It was an age of the soft quality of innocence mixed with the harder, more negative quality of arrogance. Soft and hard, rich and poor, heroism and squalor, the Titanic story had it all. It was the swift and sudden death of a dearly-held dream.

Prince Albert had said in 1851- ‘we are living in the period of most wonderful transition, which tends rapidly to accomplish the great end to which in the end all history points, the realisation of the unity of mankind.’ American author and satirist Mark Twain called it ‘the gilded age’, beginning in the second half of the 19th century and by century’s end having blossomed into a social gospel, a way of living, where man had defeated nature and heaven on earth was quite possible. Perhaps we could even outdo God. Life expectancy was rising, and technology (guided by man) was seen as a salvation or panacea for everything.

Ship-building was the space race of the early 20th century, and competition for the transatlantic passenger trade had become intense. The tremendous recent advances in technology had allowed for greater world-wide communication, the emergence of a global economy and international trade, and also increased opportunities for world travel. This travel was undertaken by many for pleasure, but there was also a mass migration in progress, with hundreds of thousands relocating to the Americas to start a new life in the hopes of increased prosperity. Britain had long dominated the waves both militarily and with its merchant fleet, almost exclusively having, through its premier steamship lines Cunard and White Star, the world’s largest, fastest and most prestigious ships in the second half of the nineteenth century. However, a pair of German steamship companies, backed by their young, energetic and ambitious Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, had by century’s end unleashed a stream of super-large, super-luxurious and super-fast liners onto the North Atlantic shipping lanes that trounced their British compatriots. Since ocean liners were such a powerful symbol of a nation’s prosperity, the British press and public were up in arms, and White Star’s responsibility to respond to this rested squarely on the shoulders of the company’s founder, Thomas Henry Ismay.

The White Star Line had gone bankrupt when Ismay had taken it over in 1869 with a capital of 400,000 pounds. Although the Cunard already had nearly 30 years experience in the Atlantic trade, Ismay’s company had caught them up by the end of the century, when the two compaies shared the pride of the British Empire’s mercantile industry. White Star’s first major ship of this era was the Oceanic of 1899, which was launched just prior to Ismay’s death in November of that year. The company now came under the watchful eye of Thomas’s son J. Bruce Ismay, who was tasked with keeping ahead of both his German rivals and Cunard. As the new century dawned, White Star unleashed its ‘big four’, named the Celtic, the Cedric, the Baltic and finally in 1907 the Adriatic. Each was the largest in the world whe it entered service and all were both comfortable and successful. However, they were not particularly fast, only reaching between them a top speed of 17 knots. Meanwhile, a recent rates war among the great steamship companies had affected the industry enough for American tycoon J.P. Morgan to buy up White Star and several other lines and consolidate them into the monster trust known as the I.M.M (International Mercantile Marine). Ismay, who now became president of the I.M.M., was a pampered, silver-spooned boy who seemed aloof to some and was meticulous and demanding but also a good businessman willing to spend money to improve things. The Cunard, aided by financing from the British government no less, set about and succeeded in building the world’s first two ‘superliners’, named the Lusitania and Mauretania and both launched in 1906. They were simultaneously the longest, tallest and largest moving objects ever built. They were the first vessels to top 30,000 gross registered tons and were nearly 800 feet in length, with the Mauretania just slightly edging out the other vessel on both counts. Their unprecedented size gave more space over for the use of their passengers, which made them as luxurios as – or perhaps even more than – any other ship in service. They had 4 an unprecedented 4 propellers but what really set them apart however was their six turbine engines where all others had reciprocating engines. The turbines gave each ship 66,000 horsepower with the capacity for more under ideal circumstances. Unsurprisingly, they soon set world records for speed after both entering service in 1907. Like Coe and Ovett would do in the late 1970s and early 80s, they traded this record back and forth with each new journey. The Mauretania generally kept a slight edge over her older sister, and the mark set in 1909 would prove to be the ultimate. These trifles about speed were really between the 2 crews and boat enthusiasts, because the bottom line was that these ships were tremendously popular and huge sources of revenue, as well as crucially overhauling the speed of the German ships.

- Bruce Ismay knew that his line would have to outdo Cunard to satisfy his investor Morgan. However the myth that his plan was forged with Lord Pirrie, owner of Belfast shipping firm Harland and Wolff, over dinner in 1907 would seem to be inaccurate since the loans taken by Cunard and other details of their plans for their sister ships were known as far back as 1902, including in press reports on the burgeoning ships’ specifications. In addition, Harland and Wolff was allied to some extent with John Brown & Company, who constructed the Lusiatania, and it seems absurd would wait so long to make plans. In April 1907, before the dinner was alleged to have taken place, White Star had already commissioned Harland and Wolff to design a pair of liners to counter the threat posed by the Cunard sisters. However the plan evolved, one thing that was decided early on was for the new White Star liners to eschew any attempt to match the Cunard ships for speed and instead they would spare no expense in making the most comfortable, spacious and luxurious liners possible. However, it was clear that, even if they couldn’t match 25 knots, they still needed to supersede the 17 knots capacity of their own ‘big four’. White Star set out to build 2 enormous liners, with an option for a third.

ather than tAs well as the business offered by the privileged, the booming immigrant trade had become the bread and butter of the transatlantic shipping companies and bigger ships could carry large amounts of bodies in 3rd class, known as steerage in reference to the lower deck of a ship where the cargo is stored and where their quarters traditionally were. These people wouldn’t travel in luxury but could, for an affordable price, still know the prestige of travel in relative comfort on the world’s greatest liners. In the age of optimism, thousands of people were opting to travel to the New World, where dreams would be realised, a sentiment still reflected in song lyrics over a hundred years later. Much like the pamphlets that offered vague promises of fruit-picking work for all (somewhere) in California at competitive rates in Steinbeck’s ‘The Grapes of Wrath’, the talk was of this magical place where you could surely transform your life if you could just get there.

Harland and Wolff’s planners got to work, having to build special machinery just to put the ships together and, some felt, doing this in something of a hurry to please their main investor. In 1909, work started and the shipyard was alive with the sounds of activity, first with the Olympic and then the Titanic (the third of the ‘White Star sisters’, the Britannic, was launched in 1914), setting in motion a chain of events that would culminate in ‘the shot heard around the world’, a phrase used to describe several famous historical ‘shots’, including the ones heralding the start of the American Revolution and the one that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914. It took time in that Belfast shipyard for the ship to take shape, and for months and months in the ‘monstrous iron enclosure’ of Harland & Wolff, all that was discernible was iron scaffolding. At that time, all of Belfast was aware of and many involved in the building of the ship. Overtime was willingly worked and people talked excitedly and often about the vessel-in-progress. Ships were built by hand in those days and it was a personal thing, Titanic’s spell starting to work its magic even before the completion of its construction. Chief Designer Thomas Andrews, who had a real feel for the labour involved, would walk around with his plans in his pocket talking to the workers and was no doubt constantly engaged in ironing out wrinkles. The steel skeleton finally started to take shape and when the ship was finally unveiled for its launch at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast on May 31 1911, it towered over the surrounding buildings and dwarfed the mountains by the water. The rudder was the size of an elm tree, the propellers like windmills. The giant, reciprocating engines, triple-screw 3-propeller design and 29 boilers, attracted the awestruck imagination of the ship-building trade journals. It was ‘Shipbuilder’ magazine who in 1911 declared the ship to be ‘practically unsinkable’, the main reason being that it could float even if 4 of its 5 watertight compartments leading back from the bow were flooded from a head-in collision. There were also watertight doors separating each compartment that could be closed with the mere flick of a switch.

On May 31st 1911, the day of Titanic’s launch, R.M.S. Olympic was delivered to the White Star Line. The 2 ships were considered sister ships and virtually identical, but Olympic’s first voyages allowed Ismay to ask for amendments to be made to Titanic to increase her tonnage and make her the largest ship afloat. Other touches added were warm running water in certain cabins and cigar holders in the bathrooms. In general, the deck space on the Olympic was considered excessive and more first-class rooms could be built on some of that space. The furnishings and other luxuries made Titanic an improvement over its sister, perhaps the most significant being the 2 private parlour suites, each containing a 50-foot private promenade with living-rooms, bedrooms and fully-equipped bathrooms, and costing as much as 4,350 dollars (which equates to an incredible 114,000 dollars in 2019) for a one-way trip in the high season. J.P. Morgan himself was meant to occupy one of these suites on the maiden voyage but cancelled at the last minute, fuelling multiple theories which will be referred to later. As well as the 16 regulation lifeboats, Titanic exceeded expectations by also including 4 collapsible boats. The total lifeboat capacity was a seemingly large number of 1,178, but that number was in fact less than a third of the maximum capacity for passengers and crew. At this point, it must be noted that the required lifeboat capacity was adhering to 1894 regulations for ships of around 10,000 tonnes, compared to Titanic’s 46,000. It was all measured then by cubic feet, and a liner of anything like Titanic’s size had never been envisaged in 1894. Harland & Wolff’s original design had called for 48 boats but when Ismay opted for the regulation number, preferring to use up space with passenger-friendly luxuries, their Managing Director didn’t press the point. Of course, to its passengers, crew and creators, the ship itself was the lifeboat, the small boats being more a kind of public relations symbol. The Titanic had 2 sets of 4-cylinder engines each driving a wing propeller and a turbine driving the central propeller, this combination giving the ship 20,000 registered horsepower. At full speed, she could make 24-25 knots. She had a double bottom divided into 16 watertight compartments and formed by 15 watertight bulkheads (upright partitions separating compartments), curiously not extending very far up the ship. The 1st 2 and last 5 went only up as far as ‘D’ deck (the highest deck of course being ‘A’ deck), while the middle 8 only went to ‘E’ deck. It hardly mattered though since nobody could imagine any 2 compartments flooding and she’d already been deemed to be unsinkable.

After completing her rather less than thorough sea trials the previous day, Titanic eased out of Belfast Harbour on April 2nd 1912 bound for Southampton. This was a big event with people waving off the ship but laced with a tinge of sadness after 4 years of work for that part of the process to be over. At Southampton, which had had a port for thousands of years and whose entire existence was bound up with the sea, she would undergo final tests and then pick up the majority of her passengers and crew in preparation for her maiden voyage. The Waterloo-Southampton trains were rammed in the hours and days leading up to the voyage, and the opulence of the liner and the famous passengers only added to the prestige and sense of occasion. The great ship blew its whistle, sirens went off and people rushed to make their appointment. It should be noted that there were a few dissenting voices who were uncertain about this huge and unknown ship on its maiden voyage, and survivor Ruth Becker remembers her mother being nervous. Survivor Eva Hart’s mother had a premonition, feeling that calling a ship unsinkable was ‘flying in the face of God’. Following the disaster, and when all the information about both victims and survivors was made public, the sheer diversity of people was one of the things that quickly caught the imagination of even those who had nothing of any kind invested in the ship. The whole microcosm of Western society lay nearly 3 miles down at the bottom of an ocean whose vastness was, as earlier noted, quite impossible to comprehend. The 300 luminaries of the day dominated proceedings of course, and the net worth of what Wall Street called the ‘millionaire special’ was over 500 million in 1912 dollars, a staggering 13 billion and more in 2019. Among the famous names, who were the pop stars of their day, were millionaire playboy Benjamin Guggenheim, Mr and Mrs John B. Thayer, he the President of the Pennsylvania railroad, Presidential Military Aide Archibald Butt and Mr and Mrs Isidor Straus, co-owners of Macy’s. John Jacob Astor and his wife were not yet on the ship at Southampton and as we know J.P. Morgan cancelled at the last minute, becoming a key part of the ‘Titanic Conspiracy’, whose several separate strands included theories that Morgan knew that the ship had been swapped for the Olympic and was going to be sunk on purpose as an insurance scam, so cancelled his ticket. Another theory proposed later was that some of the luminaries, including the richest of them all Astor, were (unlike Morgan) opposed to the creation of the Federal Reserve, which despite its government-sounding name was privately set up after being planned at a secret meeting on Jekyll Island, Georgia in 1910 and has to many people had a ‘license to print money’ as well as setting interest rates and apparently manipulating the money supply without audit ever since.

A 3rd-class berth on Titanic was comparable to 2nd class on a standard ship and 2nd to 1st. Besides the more famous passengers were hundreds of other families with their own stories. Millvina Dean was a baby when she survived the disaster and went on to be its final living survivor at the time of her death in 2009, just 3 years before the 100th anniversary. She was on her way to Kansas, where her father was planning to open a tobacconist’s shop. Also among the cast of characters for the drama to come was J. Bruce Ismay, who during voyages liked to alternate between being the Chairman of the line, one of the crew and ‘just another passenger’. The captain was Edward J. Smith, 62 years old, a veteran of 38 years at sea and continuing his tradition of skippering the White Star ships on their maiden voyages after having also helmed Olympic’s first trip. One claim subsequently denied by White Star was that Smith was due to retire and that he would have done so after the Titanic’s scheduled arrival in New York. Many passengers chose ships based on the captain, and this included Smith on many occasions. He was a bearded, well-decorated patriarch and well-loved by passengers and crew alike. However, a couple of quotes he’d given a few years earlier seem in retrospect to be omens of his less than decisive actions following the collision with the iceberg. In 1907, when he’d helmed ‘The Adriatic’, he’d remarked that ‘I cannot imagine any condition that would cause a ship to founder, including this one. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that’. Towards the end of his career, he was quoted as saying that his nearly 40 years at sea had been ‘uneventful, never having been near any kind of wreck or disastrous predicament’, and that he was ‘not good material for a story’. Also aboard was Thomas Andrews, Managing Director of Harland and Wolff and the Titanic’s builder, a man proud of his creation and dedicated to ironing out any kinks. He knew every detail of the Titanic, understood ships like some understand horses and was an expert at predicting how a ship would react to certain circumstances. Just as he had in the shipyard, he would be found during the voyage roaming the ship taking volumes of notes. His room was piled high with plans and blueprints and when he often dined with the ship’s surgeon, the good doctor would urge him to occasionally take a break. The vast mechanical marvel also contained a crew, many hired last-minute, who were ill-equipped for its immense size. They mostly didn’t know each other, and even experienced old hands like 2nd Officer Charles Lightoller felt overwhelmed. The deck was a 6th of a mile long, and Lightoller felt it was very hard to really know.

Just before midday on April 10th, Southampton Docks was a whirl of activity. Under a grey and foreboding sky, the cry of ‘all ashore that’s going ashore’ rang out. On the stroke of noon, the Titanic moved slowly away towards the mouth of Southampton Harbour. Suction from the huge propellers actually started to pull the ‘New York’, docked in the harbour, away from her berth. A certain collision was finally avoided but one passenger remarked that it was a bad omen. Capt. Smith was unruffled as he eased the ship out of the harbour, but his complacency would later be crucial. On the evening of Apr 10th, Titanic stopped at Cherbourg in France for passengers and mail. John Jacob Astor, recently-divorced and now hastily married to a beautiful, much younger woman, boarded the ship here. Queenstown, Ireland (now known as Cobh) was the last European stop on the 11th. There, an Irish priest would happen to snap the final pictures onboard the Titanic. At Queenstown, the last 100 of the 771 steerage passengers boarded. To summarise the classes, 1st class was (literally in this case) above everything, 2nd class aspired to 1st class status, and 3rd class people were nothing, ‘non-people’, segregated in the lower decks and not allowed to physically contact anyone on the other decks. They were treated as cattle, if at least in this case pedigree cattle. Some saw toilets for the first time and were generally seeing on the Titanic a different world to anything they’d ever known. Many had sold up for a new life in an unknown world, packing away in boxes and cases their worldly possessions to seek their fortunes, or at least a better state of survival. Excitement and nervousness surely competed in their minds as their dominant feeling. They came from over a dozen countries, and 3rd class was an exotic potpourri of customs, complexions and languages. The Irish mountains was the last the passengers would see of Europe as the ‘floating palace’ pulled away from Queenstown. For the rest of the voyage, the ship would contain 891 crew and 1316 passengers.

The officers were, in order of rank:

Captain Smith

Chief Officer Wilde

Ist Officer Murdoch (who wrote to his sister that he had a ‘queer feeling about the ship’)

2nd Officer Lightoller

3rd Officer Pitman

4th Officer Boxhall

5th Officer Lowe

6th Officer Moody

As the uneventful days of Friday 12th and Saturday 13th of April passed, a routine developed. The stokers and firemen down below sang as they worked, while Colonel Archibald Gracie and others in 1st class took advantage of the summer palace, including swimming in 6-foot deep saltwater swimming pools heated to a comfortable temperature, plus the lavish Turkish baths, cooling rooms and saunas, unheard of for a ship. Each deck was vast and had a different flavour, and a journey from the marvellous staircases in first-class, built to a standard arguably never equalled in their elegance and attention to detail, would take in all manner of impressive scenery and ‘beautiful people’. One survivor remembered thinking it was all too good to last, and Eva Hart said that her mother slept in the day and sat up every night as her premonition stayed in her mind. On the 12th, warnings were received of ice fields, which seemed to 1st Officer Boxhall ‘well to the North of Titanic’s course’. The winter of 1912 had been unusually warm and many icebergs had broken off from the Greenland course and were drifting South with the Labrador current towards the North Atlantic shipping lanes. Chief Wireless Operator John Philips and his assistant Harold Bride received at least 8 telegrams in the wireless room between April 12th and 14th warning of hazardous ice. Overwhelmed with personal messages that needed to be sent for the benefit of the illustrious passengers and which they depended on sending to get paid their fairly meagre wages, Phillips and Bride relayed these ice warnings to the bridge only periodically. The legend of Titanic trying to set a Transatlantic speed record is inaccurate and impossible when comparing its speed with that of the Lusitania and Mauretania, but it was apparently trying to overhaul Olympic’s speed of the previous year, an example of ‘beat thy neighbour’, a familiar flaw in human instincts. One first-class passenger distinctly heard Ismay talk to Smith about this beating of Olympic. Rumours notorious travel quickly on ships, and this particular one was not discouraged by Ismay. They even planned to arrive a day early for good publicity. Ismay showed (showed off?) a telegram of ice warnings as a piece of ‘inside information’, and complacency was once again in evidence.

The drama was poised to unfold.

Sunday April 14th

There were apparently ice warnings arriving from 9am and they continued through the day. Later, some of the passengers braved the bitter cold to wander out on to the deck to marvel at the spectacular sunset before enjoying a particularly sumptuous Sunday dinner. Church services were held in all 3 classes and in 2nd class the Reverend Carter, with the irony that always seems to be attached to major historical events, led the congregation in the hymn ‘For Those In Peril On The Sea’. The ice warnings collectively indicated an ice field of 80 miles directly in the ship’s path, but nobody put the messages together. The last warning in fact marked out with latitude and longitude a rectangular field of ice which the Titanic was already in, the bridge never getting that message either. By 7.30pm, the temperature was down to 39 degrees Fahrenheit, not far above freezing point. The officers were aware that the ship was likely to encounter ice before the night was over, and at 9pm Smith and Lightoller were on the bridge discussing it. Gazing out into the black night, Smith told Lightoller to let him know if he had doubts about their ability to evade possible hazards. They did everything that was expected of them by 1912 standards, and in fact may have reasoned that before wireless existed, ships hadn’t been regularly ramming into icebergs, so they could surely navigate around them. At 10pm, Boxhall relieved Lightoller, who bid him a good shift. The ship was making 22 knots, the sky was cloudless and the sea like glass. When you stood on Titanic’s decks, especially with the calm sea that existed on April 14th, you could simply never believe that, save for some throwback to a previous age with a sudden attack on the ship, the freezing temperature of the water would bear any relevance to this Sunday night for the passengers. At 10.20pm, about 10 miles away, the Leyland liner ‘The Californian’, a slow 6,000 tonner travelling from London to Boston with room for 47 passengers but carrying none, stopped due to drifting ice blocking her path. At 10.30pm, the temperature of the sea had dropped to 31 degrees, just below freezing. At 11pm, The Californian’s sole wireless operator Cyril Evans tried to contact a stressed Phillips on the Titanic about ice fields and was told to ‘shut up, I’m busy’. Evans was accompanied at that time by 3rd Officer Groves, an eager and curious young seaman, who was, as was his custom, spending time in the wireless shack catching up with the latest news and fooling around with the wireless set. Wireless was still at this time an ‘erratic novelty’. Range was short and signals hard to catch, and Phillips and Bride had been hard at it relaying the trivial and frivolous private traffic of rich passengers who couldn’t resist utilising the new miracle and sending messages back home to friends. On this occasion, such frivolities inadvertently spelt the doom of 1,500 people, mostly those in an entirely different social class and world, not to mention the demise of the ‘age of innocence’. The operators, working 14 hours a day on 30 dollars a month, were stressed and tired as the in-basket piled up with paper, and just when they were getting on top of it, the Californian, so close that she ‘blew their ears off’ with messages about ice warnings, bothered Phillips and received his terse response. Evans hung up his headset at 11.35 and turned in for the night. He would be awoken 6 hours later with the most incredible news that anyone on the North Atlantic that night could imagine.

By 11.40pm, Titanic’s passengers were mostly cuddled up in their cosy (and not quite so cosy) cabins while a few card players and society gentleman lingered in the 1st class smoking room. In the crow’s nest, the shivering lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee peered into the night. It was calm, clear, very cold, moonless, with a cloudless sky and the stars shining. The Atlantic Ocean at that moment looked like polished plate glass. The lookouts had been warned by Lightoller to ‘keep a sharp look-out for ice, particularly small ice and growlers’ but after an officer reshuffle at Southampton, nobody seemed to know where the binoculars were stowed. In the event, they may not have done any good on a night that was pitch black save for the stars in the sky and the ship’s lights. As the largest and most glamorous ship in the world travelled through the water at 22 knots (25.3 mph) on Sunday 14th April 1912, a shape got larger and closer, spotted by 25-year-old Fleet, who then telephoned the bridge with the immortal words, ‘iceberg right ahead’. Because the water was so flat, they didn’t see the iceberg until it was too late, since waves need to break at the base of a berg for it to be seen from a distance. As the ice drew nearer, the ship turned, ordered by 1st Officer Murdoch hard to starboard, which actually meant an instruction to move the tiller (steering lever) to starboard in an attempt to turn the ship to port, a procedure that took a full 37 seconds. It was incredibly cumbersome trying to turn such a huge liner in a hurry, but as the bow sluggishly swung to port, the lookouts thought for a moment that they might just avoid a collision. Alas not. Ice glided along the starboard side as the iceberg towered 100 feet above the water, meaning that there would be around 800 feet of it below the surface. A monster from nature. Stewards gossiping in the 1st class dining-room heard a faint, grinding, rumbling, vibrating jarr coming from deep below the ship, rattling the silver already set for breakfast. Had the ship dropped a propeller blade? To some, it seemed like a heavy wave had struck the ship. A bump was heard on the opposite side of the ship from the collision by Eva Hart’s mother, she of the premonition. As ever, she was fully-dressed and ready to leave her cabin if required. Some passengers who knew what had happened heard a dull thump, felt the ship quiver, heard a scraping noise along the ship’s side and saw a wall of ice glide by and chunks of ice get thrown onto the deck. Some on deck saw the berg in the night, but the excitement came and went quickly and it was too cold to stay out any longer on deck. Some ice landed on the starboard well deck, which was the steerage area’s recreation space, and 3rd class passengers threw some at each other or played football with it. One passenger took a chunk to use in his highball, while many terrified steerage families carried all their worldly possessions onto the 3rd class promenade area.

Murdoch had already ordered the ship stopped, but the engine-room telegraph handle wasn’t turned to stop until after the collision, and the emergency watertight doors were then closed. Murdoch ordered hard to port to try and fishtail the ship past the berg but it was too late. The ice had already scraped against the ship’s steel hull, buckling plates, popping rivets and apparently creating a large gash below the waterline. Captain Smith rushed onto the deck and was told by Murdoch what had happened. Down below in boiler room 6, the gash caused by the berg seemed to cause the starboard side to give way and a fat jet of sea water rushed into boiler room 5, with Second Engineer Hesketh and Leading Stoker Barrett escaping just before the room’s watertight door closed. An avalanche of coal had also poured out of a bunker with the impact of the collision. It should be noted the contrast between what was experienced and known about down below and what was happening on the upper decks. Just as ‘real life’ is said to involve inevitable hardship, and the tourist industry tends to want to hide some of the harsh realities of poor areas from moneyed holidaymakers, the ‘real situation’ is often known more intimately by the humble workers while the rich are the most unaware and out of touch. To the rich on the top decks of the Titanic, the collision was a trifle, a slight jarr, something that might spill one’s drink but no more, while down below the workers were well aware of the gallons of water pouring in by the second. The forward steerage cabins certainly knew something was terribly wrong as well, and the collision had been to them not a jarr but a tremendous noise that sent many of them tumbling out of bed. Up top, rumours started to spread about the dropped propeller blade and the ship stopping to prepare to go around the iceberg. Nearby, The Californian had noticed a blaze of deck lights showing a large steamer. Captain Stanley Lord ordered contact by Morse lamp. At 11.40, 3rd Officer Groves saw the big steamer stop and most of the lights go out, not unusual as this was often done to encourage passengers to turn in for the night. It didn’t occur to Groves that the lights hadn’t gone out but that the ship had in fact veered sharply to starboard after her initial turn to port and was now stopped and facing northward almost directly toward the Californian. Passengers on the Titanic were seized with a restless curiosity, particularly since the journey had been boringly uneventful, ‘a picnic’ for the workers. At 11.50pm in the first 6 of the 16 watertight compartments, water was rushing in so fast that the air rushed out under tremendous pressure. Green sea water swirled around the steps of the spiral staircase leading to the passageway connecting the fireman’s quarters and the stokeholds, where the boilers were located and fired. In the 3rd compartment aft closest to the bow and containing the cheapest accommodation on the ship, a passenger saw water seeping in under the door and up to his shoes. The post office, taking up 2 deck levels, had workers dragging 200 sacks of mail to the sorting room with water sloshing around their knees. The water rose up to the deck above in a matter of minutes and soon after that, the lights went out in boiler room 5.

On the bridge, Captain Smith, considered a natural leader and adored by all for his combination of firmness and urbanity, must have been wondering how this night would end. 4th Officer Boxhall was sent to do a quick check below but didn’t go down far enough and reported no problems. The carpenter was then sent to sound the ship and emerged gasping ‘she’s making water fast!’. The mail hold was filling rapidly and had already been abandoned. Ismay, demanding to be given information, was told of the iceberg and the serious damage to the ship. Thomas Andrews ran into Capt. Smith while they were on separate inspection trips and they then took a tour of the ship together, seeing the water coming in at various points, including the squash courts and the rapidly-flooding mailroom. The working alleyway on ‘E’ deck was a broad corridor and the quickest route from one end of the ship to the other. It was quickly filled with pushing and shoving passengers, some of them stokers forced out of boiler room 6 but the majority steerage passengers working their way aft, laden with boxes, bags and trunks. Engineers were struggling to make repairs and get the pumps going. Far above on ‘A’ deck, first-class passenger Lawrence Beesley found his feet not falling right on the steps, straying forward as if the steps were tilted down towards the bow. The ship was, as others noticed, ‘listing’, 5 degrees to starboard to be precise. Andrews’s quick calculations, which he relayed to Capt. Smith soon after midnight, reported water in the forepeak (the furthest forward lower compartment next to the bow), all 3 holds (the spaces for carrying cargo), the mailroom and boiler rooms 5 and 6, reaching 14 feet above the level of the keel (the structure around which a ship’s hull is built) in the first 10 minutes. It was thought for years that a 300 feet gash had opened up the 1st 5 compartments to flooding, but modern ultrasound surveys have found that the damage actually consisted of 6 small openings in an area of the hull covering only 12-13 square feet and about 10 feet above the bottom of the ship. In any case, Andrews explained to Smith that Titanic couldn’t possibly float with her first 5 of 16 watertight compartments flooded. The bulkhead between the 5th and 6th compartments went only as high as ‘E’ deck so the flooding of the 5 compartments would sink the bow so low that water from the 5th would overflow into the 6th, then the 7th and so on, rather like an ice cube tray. It was a mathematical certainty, flying in the face of ‘Shipbuilder’ magazine’s 1911 confidence in her unsinkability. A little while after, Capt. Smith was standing on the deck of a liner twice as big and twice as safe as the Adriatic and he’d just been told that it couldn’t float. At this point though, it was curiosity rather than panic that brought 1st and 2nd class passengers out onto the frigid deck, where they chatted and waited for an official explanation.

At 12.05am, Smith ordered Chief Officer Wilde to uncover the lifeboats, 1st Officer Murdoch to muster the passengers and 4th Officer Boxall to wake 2nd Officer Lightoller and 3rd Officer Pitman. Smith next went to the wireless shack containing John Phillips and Harold Bride. Phillips had become so tired that Bride had offered to relieve him at midnight, 2 hours before his shift was due to start. He’d just started to take over when suddenly in came the Captain with the grave news. The Captain instructed them to ‘send the call for assistance’, and at 12.15 Phillips was back and tapping out the letters CQD, at that time the international call of distress, over and over again into the cold blue Atlantic night. At that precise time on the Californian, 3rd Officer Groves listened in on the headphones. He was getting good at reading simple messages but, not knowing the equipment well, had failed to wind up the magnetic detector and heard nothing. All over the Titanic, word started to spread, fairly quietly, without bells, sirens or a general alarm, and mostly amounting to word of an an inconvenience that could delay the arrival in New York by a day or so. The ladies were ordered on deck with lifebelts on. At this point, readers should try to imagine these people in their warm, comfy cabins being ordered onto the freezing deck for seemingly no reason. This enormous ship, aside from a slight list, appeared undamaged, and now they were about to be told that they were required to be lowered into small rowboats ‘as a precaution’. Passenger Lawrence Beesley was standing on deck before it was crowded and later said that ‘The Titanic lay peacefully on the surface of the sea, motionless and quiet. To stand on the deck, many feet above the water lapping idly against her sides, gave a wonderful feeling of security. To feel her so steady and still was like standing on a large rock in the middle of the ocean’. At 12.15am, it was hard to know whether to joke or be serious. Should locked doors be smashed open to get to the upper decks for fear of reprisals in New York? At this point, it was early in the slow inevitable creep towards death by freezing water and nobody knew for sure that any talk of this sort would be a total irrelevance. Some did move quickly, others were more complacent, just like the age. Some took possessions of monetary and/or sentimental value, including the famous wind-up, musical toy pig of fashion journalist Edith Russell, some didn’t. One passenger took a revolver and a compass. Some dressed well, including Denver millionairess Molly Brown, who looked stylish in a black velvet 2-piece suit with black and white silk lapels. In steerage, the single men and single women had been quartered at opposite ends of the ship. Inevitably, there had been some couplings and flirtations during the journey and some of the men travelled to where the women were.

Into the bitter night, the whole crowd milled, each class keeping to their own decks. 1st class was in the centre of the ship, symbolically at the centre of things, 2nd a little aft and 3rd at the very stern or in the well deck near the bow. Quietly, they stood around waiting for the next orders, reasonably confident yet vaguely worried, eyeing themselves in lifeboats with uneasy amusement and making half-hearted jokes about life jackets being ‘the latest thing this season. Everyone’s wearing them!’, which was almost true on the Titanic by this point. Colonel Archibald Gracie suggested that he cancel his appointment with the squash pro for the next morning. Without an alarm or P.A (public announcement) system on the ship, there were no words that could be clung to to make the situation clear, and at 12.30am, 50 minutes after the collision and still 1 hour 50 minutes before the sinking, everything was in a state of limbo. Some passengers went to the gymnasium and were encouraged to try out the equipment while waiting for further instructions. John Jacob Astor sat casually on a mechanical horse, cutting open a life jacket to show his wife what was inside it. Meanwhile, the crew moved swiftly to their stations, the boat deck teeming with seaman, stewards and firemen ordered up from below. The passengers were mustered to go onto the boat deck with a sense of urgency ranging from polite knocks on doors in 1st class to pounding on doors and a shouted order to get out in 3rd class. Back in 1st class, a Frenchman called Michel Navratil, travelling under the alias of Michael Hoffman, woke his 2 young sons, who he was kidnapping from their mother in a bitter and emotional custody battle. 2nd officer Lightoller was a late arrival to the drama, having woken up from his slumber when the ship hit the iceberg but returned to his cabin, being off-duty. He could hear the roar of the funnels blowing off steam and the rising sound of voices and at 12.10am was summoned by Boxhall. Lightoller was cool, diligent and cautious, the perfect 2nd Officer. There were 16 numbered wooden lifeboats, 8 on each side of the ship, plus 4 canvas ‘Englehart’ collapsible lifeboats, lettered A to D. In total, the boats could hold 1,178 people out of 2,207 people on board. None of the passengers and few of the crew were aware of this discrepancy, but were of the mind that ‘God himself couldn’t sink this ship’, as one of the deckhands had said to a lady passenger while carrying luggage aboard back in Southampton.

There’d been no boat drill so there was an element of confusion, but the crew were professional and gradually the canvas covers of the boats were removed. One by one, the cranks were turned, the davits creaked, the pulleys squealed and the boats slowly swung out free of the ship. The going was slow. Lightoller was in charge of the port side and attempted to get the women and children loaded in. The response was anything but enthusiastic. Why trade the bright decks of the Titanic for a few dark hours in a rowboat? Astor ridiculed the idea, saying they were much safer on the ship. Once passengers were in the under-filled boats, they had to be lowered 60 feet to the water by crewmen who hadn’t had the benefit of a practice run, and it was a nervy and tense procedure which resulted in near-accidents and drama. On the starboard side, things moved quicker but Ismay rushed to and fro, urging the crew to move faster. 3rd Officer Pitman, not knowing Ismay, shrugged off this ‘officious stranger’ until he realised who Ismay was. On this side, a few couples and single men were allowed on the boats. ‘Women and children’ first was the rule. As number 5 creaked downward, Ismay continually chanted ‘lower away’ while waving one arm in huge circles and hanging onto the davit with the other. 5th Officer Lowe exploded at him, ‘if you’ll get the hell out of the way, I’ll be able to do something’. The abashed Ismay walked away and some gasped at the 5th Officer berating the Chairman of the line, remarking that there would be a ‘day of reckoning’ in New York. The process of loading the lifeboats would take 1 hour 25 minutes in total, from 12.40am to 2.05am, 15 minutes before the ship’s final plunge. The first was lifeboat 7 on the starboard side, launched with 28 on board out of a capacity of 65, a pattern that would continue.

There was a soundtrack to all this activity as the ship’s band, off duty when the collision occurred, played initially in the first-class lounge and later on the boat deck. The band was the best on the Atlantic, the White Star having raided the Mauretania for the bandleader. The pianist and cellist had been easily wooed from (ironically) the Carpathia, the ship that some but not them would be seeing again in a few desperate hours. There were 8 musicians in total and the beat was fast, the music loud and cheerful. From a modern vantage point, the music seems to have given the real events happening at this point even more of the feel of a movie. Still the truth hadn’t dawned, one old seaman stating that the ship was good for 8 hours yet, and inconvenience was still the prevailing feeling of many. In the nearly-empty smoking room on ‘A’ deck, 4 men deliberately avoided the noisy confusion of the boat deck. At the very stern, Quartermaster Rowe paced around, having heard nothing for an hour before suddenly seeing a boat being lowered away. He was ordered to the bridge with a box of 12 rockets. Some watched the water rise and seemed to sense what was happening. Thomas Andrews ordered a stewardess to put on her lifebelt ‘if you value your life’. The charming and dynamic Andrews understood people well and was everywhere, handling people differently depending who they were. He kept the bad news quiet to most or played it down but told John B. Thayer that he didn’t give the ship much more than an hour to live. It must have been horrific and highly surreal for Andrews to be walking around inside the ship, knowing that all the fixtures and fittings, the magnificently ornate decorations and everything else would, in 1-2 hours, be lying at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. That was a certainty, now all that lay in the balance was the fate of the 2,200 people on board. Down below, the door to a flooding coal bunker burst open from the tremendous pressure of the inrushing water. In the wireless room, around the time that the first lifeboat was launched, Phillips was working away, sending the new SOS signal as Bride rushed to and from the bridge with news. Sending this signal had been Bride’s bright idea, as it had recently been agreed by an international convention for its ease of understanding. Phillips laughed at Bride’s joke that ‘it may be your only chance to use it’.

At 12.45am, the first SOS in history was sent. Curiously, Captain Smith had also laughed at Bride’s joke, and the Captain’s behaviour was curious to say the least. Lightoller later testified that Smith had not been barking out orders with urgency and was in fact hesitant throughout. The officers on more than one occasion had to suggest to him the next move, and it appears that some complacency was in evidence, or perhaps just a lack of experience of this situation despite his many years at sea. Following the initial CQD, the Frankfurt had responded quickly at 12.18am but without giving a position (shortly after, it was learned that she was 150 miles away). The night crackled with signals as the news was passed along and spread in ever-widening signals, including by Cape Race, the lighthouse which had a Marconi wireless station set up inside it. Harold Cottam of RMS Carpathia had been on the bridge when the first CQD had been sent and at 12.25 he was about to turn in and was undressing when he decided to have a last listen on his rather primitive wireless set (range-approximately 250 miles) and received the message from Phillips ‘come at once, we’ve struck a berg. It’s a CQD, old man. Position 41.46N, 50/14W’. There was a moment of appalled silence before Cottam, still half-dressed, quickly rushed to the bridge to inform 1st Officer Dean, and then woke Captain Arthur Rostron. They were 58 miles away. The Carpathia was an intermediate-sized Cunard liner of 13,500 gross registered tons and with a maximum speed of around 14 knots (16 m.p.h.). It was just over half the length of the Titanic and had left New York on April 11th on the Mediterranean run, bound for Gibraltar, Genoa, Naples, Trieste and Fiume. Her 150 1st-class passengers were mostly Americans following the sun in this pre-Florida era, while the 575 steerage passengers were mostly Slavs and Italians returning to their native lands . Captain Rostron had been at sea for 27 years but was in only his 2nd year as skipper and his 3rd month on the Carpathia. When he was awoken with news of the CQD, he acted fast, ordering the ship turned and urging Cottam to confirm his absolute certainty of the message. Rostron worked out his ship’s new course but at 14 knots it would take 4 hours to reach Titanic. Rostron told the Chief Engineer to call out the off-duty watch, cut off the heat and hot water and pour every ounce of steam into the boilers. Dean was told to knock off all routine work and organise the ship for rescue operations, opening all gangway doors and swinging out the boats to receive passengers. Among Rostron’s other incredibly detailed instructions were for first-aid stations to be set up in each dining saloon and all restoratives and stimulants collected. Passengers would be divided into classes, and soup, coffee, brandy and whisky were prepared for survivors as well as 3000 blankets. Rooms were converted into dormitories. Rostron also urged everyone to keep quiet so as not to have the sleeping passengers underfoot. Stewards were stationed on every corridor to tell any curious passengers that there was no trouble and that they should return to their cabins. The ship sprang to life and the coal was poured on in the engine rooms. The old ship got up to an unprecedented speed, driving ahead. At 1.15am the stewards were mustered to the main dining saloon and informed what was happening by their Captain, whose words seemed to be so typical of that era which would soon sink without trace. ‘Every man to his post and let him do his full duty like a true Englishman. If the situation calls for it, let us add another glorious page to British history’. Rather less grandly, Rostron charged all with ‘the necessity for order, discipline and quietness and to avoid all confusion’. From now, the formerly-groggy men who received these orders were sleepy no more. They all hastened double-quick to carry out the Captain’s orders.

The Olympic, the Titanic’s sister ship, had a strong signal and a close bond with the Titanic but was 500 miles away. However, there was another ship whose lights winked just 10 or so miles off the Titanic’s port bow, and 4th Officer Boxhall saw clearly through the binoculars that it was a steamer. As he tried to get in touch with the Morse lamp, he felt he saw an answer but could make nothing of it and decided it must be her mast light flickering. Captain Smith ordered Quartermaster Rowe to fire the distress rockets every 5-6 minutes, and at 12.45am, 5 minutes after the first lifeboat was plunged into the Atlantic, the first rocket shot up from the starboard side. A blinding flash seared the night far above the masts and rigging, then burst and a shower of bright white stars floated slowly down toward the sea. Some of the children must have marvelled at this fireworks display which, along with the uptempo ragtime music, gave the impression of a macabre party. Apprentice James Gibson on the bridge of the Californian saw that the mysterious steamer hadn’t moved for an hour. He could make out her sidelights and a glare of lights on her aft deck and at one point felt she was trying to signal with her Morse lamp. He tried to answer with his own lamp but soon gave up. At 12.45am, 2nd Officer Herbert Stone saw a sudden flash of white light and thought it strange that she would fire rockets at night. On the Titanic, even those passengers who were land-lovers understood what rockets meant, and the atmosphere took another turn. Some wives refused to go, some went willingly, and there were many farewells. Arthur Ryerson told his wife that he ‘must obey orders’ and that ‘I’ll be alright’, perhaps the only way to get some of the women in. Lucien Smith assured his wife that ‘everyone will be saved’. Captain Smith shouted ‘women and children first’ into his megaphone. Mrs Isidor Straus famously proclaimed that ‘I’ve always stayed with my husband so why should I leave him now?’ The Strauses had been together for 41 years and had written to each other whenever they were apart. They’d been through the ashes of the Confederacy, started a small china business in Philadelphia and then built Macy’s into a national institution. Now they were in the ‘happy twilight’ of successful life and it all culminated with the famous maiden voyage of the enormous, glamorous liner. ‘Where you go, I go’, said Mrs Straus. Mr Straus was offered a boat with his wife but refused to go before the other men. They sat down together on deckchairs. Most of the women did go, either wives or single women accompanied by single men who, in the tradition of the time, had volunteered to look out for these unprotected ladies at the start of an Atlantic voyage. By 1am, even the carefree were feeling uncertain. Passengers who went back for their valuables found their cabins underwater. Time was running out, and Andrews helped to urge the women to get in the boats. The rockets were fired and heard at regular intervals and there was both urgency but still relative calm, most people’s growing unease internalised. Chief Officer Wilde, 2nd Officer Lightoller and 1st Officer Murdoch fetched firearms in case they needed them.

The boats were being swung out, filled and dropped into the sea quicker now but also more sloppily, the sense of urgency slowly growing but still with some caution on the part of the officers, lest urgency spill over the fine line into panic. At this point, the water was climbing up the stairs of the emergency staircase that ran from the boat deck all the way down to ‘E’ deck. Some passengers lost their nerve trying to climb into the boats, some shrieking hysterically and some losing their footing and falling into the boats. A shortage of trained seaman made the confusion worse, many of the best men being used to man the early boats and other old hands engaged on other jobs. Lightoller was rationing the seaman now, 2 to each boat. A yachtsman who swung himself out on the forehead fall onto a boat which had only able seaman was the only male allowed by Lightoller into a boat on the port side, as the ‘women and children first’ mantra may have got skewed to ‘women and children only’, while Murdoch on the starboard side let more men in, especially if they belonged to 1st and 2nd class. Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon and his wife and her secretary Miss Francatelli asked to enter boat 1, which infamously left with just 12 people out of a possible 40 and only 2 of them women. Greaser Walter Hurst caustically remarked that ‘if they’re sending the boats away, they may as well put some people in them’. It is well-known that none of the boats were filled to anything like capacity, and there may have been a thought that they might hover around the ship and return later, but the vast majority never did. Down in ‘E’ deck, many 3rd class passengers got nowhere near the boats, a swarm of them milling around the foot of the main steerage staircase. They’d been there ever since they’d been called from their cabins. Amid the low ceilings, naked light bulbs and scrubbed simplicity of the plain white walls, they looked more like inmates than passengers as they swarmed around, many of them Finns and Swedes and others who didn’t speak English. When at 12.30 orders were received to put the women and children in the boats, they had to be escorted in small groups on the long journey through the maze of passengers normally sealed off from 3rd class. Up the broad stairs to the 3rd class lounge, across the open well deck, past the 2nd class library and into 1st class quarters, where they were stopped in their tracks and looked in disbelief at the magnificent surroundings. While they were helped to some extent, it is also thought that the majority were ‘neglected to death’. Getting them in the boats still wasn’t easy. Other steerage passengers found their own way to the boats, some barriers that separated them off from the other classes falling down, most knocked down. Like a stream of ants, they found their way under their own steam through the 8 decks and seemingly endless passageways to the boats, now their only salvation. Some got lost and resorted to using the emergency ladder meant for the crew’s use. This ladder was near the brightly-lit windows of the 1st class a la carte restaurant. They looked in and marvelled at the tables beautifully set with silver and china for the following day. Some beat on the barriers, demanding to be let through, but still the regulations were followed despite the fact that soon these rules would be rendered completely irrelevant. Think of someone probably about to die. At some point every rule holding him back and all the preconditions of having to live in a society disappear. For every steerage passenger who made it through, there were hundreds milling around aimlessly at various points and some still in their cabins. Staff in the 1st class restaurant were neither passengers nor crew and not employed by the White Star line. They had no status and were also French and Italian, objects of deep Anglo-Saxon suspicion in 1912. They never had a chance, herded together in their quarters on ‘E’ deck. Only 3 made it because they happened to be in civilian clothes. Down in the engine room, there was no thought of getting away as they struggled desperately to keep the steam up, the lights lit and the pumps going.

One by one, the boats rowed slowly away from the great ship, oars bumping and splashing in the glass-smooth sea. All eyes in the boats were glued on the Titanic. Her tall masts and the 4 big funnels stood out sharp and black in the clear, blue night. The bright promenade decks and the long rows of portholes all blazed with light. They could see the people lining the rails and could hear the ragtime playing in the still night air. From this perspective, it seemed impossible that anything could really be wrong with this great ship yet there they were and there she was, well down at the head. Brilliantly-lit from stem to stern, she looked like a sagging birthday cake. The boats moved clumsily away, some told to make for the steamer whose lights shone in the distance, agonisingly close. Captain Smith told the passengers of boat 8 to go towards the boat in the distance, land its passengers and go back for more. Quartermaster Rowe was told to send a Morse message that ‘we are the Titanic sinking, please have your boats ready’. Rowe called again and again to no avail. On the Californian, 2nd Officer Stone and Apprentice Gibson counted 5 rockets by 12.55 and tried the Morse lamp. At 1am, there was a 6th rocket and at 1.10am Gibson informed the sleeping Captain Lord, who advised him to keep on Morsing. Stone noted that the ship looked ‘very queer’, clearly listing, and her red side light had disappeared. The other ships didn’t seem to understand, the Olympic asking as late as 1.25am if the Titanic was coming to meet them. The Frankfurt asked for more details and Phillips angrily tapped back, ‘you fool. Stand by and keep out!’ Capt. Smith entered periodically to warn that the power was fading and later that the water had reached the engine room. On the Carpathia, Harold Cottam’s set in his small wireless shack was miserable, with a range of just 150 miles, so when he stopped receiving from Titanic, he couldn’t know for sure what had happened. He heard her report at 1.10 that they were ‘sinking head down’, at 1.35 ‘engine room flooded’ and finally at 1.50am the final plea ‘come as quickly as possible, old man. The engine room is filling up to the boilers’. After that, a deafening silence. Cottam hunched tensely over the set, still only in his shirtsleeves despite the cold.

By now, the roar of steam had died, the nerve-racking rockets had stopped but the slant of the deck was steeper and there was an ugly list to port. By this point, there was no trouble persuading people to leave the ship. A young boy used a woman’s shawl and got on a boat in disguise. Lifeboat 14 was rushed by a wave of men being beaten back with the tiller. Lowe threatened them with his gun and fired 3 times along the side of the ship as the boats dropped down to the sea. A big mob pushed and shoved around Collapsible boat C but the officers finally got it off. Bruce Ismay was around this boat, calmer than before and helping to get the boat ready for lowering, now every inch a member of the crew. At the last moment, he climbed into boat C, just 1 passenger of 42 in the boat. Inside the ship, one passenger stayed sitting in the 1st-class smoking-room reading alone. Reverend Bateman called to his sister-in-law entering a boat that ‘if I don’t meet you again in this world, I will in the next’, taking off his necktie and tossing it to her as a keepsake. Benjamin Guggenheim and his valet took off their life jackets and dressed in their best, ‘prepared to go down like gentlemen’. What choice the valet had in what was basically an act of suicide is something worth pondering. At the point where it became ‘every man for himself’ a little later, all semblance of duty and employer/employee relationships quite rightly went out the window. As Titanic’s life afloat ebbed away, the passenger areas inside the ship started to flood. The water, which up to now had only existed outside the ship, was now inside and creeping up the staircase as the ship got lower and lower. The forward, first-class staircase went down to ‘E’ deck, and to stand on the boat deck and look over the balustrade into an open well through 5 decks and see green sea water swirling around, getting higher and higher, must have been a terrifying moment for anyone witnessing it. As the number of boats left to be packed and lowered away dropped to 2, the water had now reached ‘C’ deck, rising fast. Paradoxically, all the lights still burned bright, illuminating the clear night, and the music was up-tempo, lively ragtime. 2nd Officer Lightoller, steadfastly sticking to what seemed like a system of ‘women and children only’, wouldn’t even let John Astor, the richest man on the ship, into Lifeboat 4, so stern was his policy. Astor asked the number of the boat, either to locate his wife or (to Lightoller’s mind) to make a complaint later. At 2am, there was only Collapsible D left, ready for loading. The lights were beginning to glow red and chinaware could be heard breaking somewhere below. One male passenger drained a full bottle of gin and later survived. Lightoller took no chances with the last boat, since there were now 47 seats for over 1,500 people even though most had moved aft. He had the crew lock arms in a wide ring around the boat, only letting the women through. 2 baby boys were placed in the boat by their father, Mr ‘Michael Hoffman’, the Frenchman who was kidnapping the children from his estranged wife. At 2.05am, the boat was lowered into the sea.

With the boats gone, a curious calm came over the ship. The excitement and confusion of that phase of the drama were over, and those left behind stood quietly on the upper decks, trying to keep as far away from the rail as possible. One man opened his wallet and poured his money over the side of the ship while others played on the gymnasium’s equipment and one lady played the piano, waiting for the end. As the freezing water appeared to be rising towards the boat deck (as opposed to the boat actually sinking into it), there were hopeless efforts to clear 2 more collapsibles lashed to the roof of the officers’ quarters. Passenger Jack Thayer felt far away, as though he were looking on from some other place. 60 feet below the deck, deep down in the boiler rooms, the engineers and firemen toiled away in the stifling and dangerous heat, trying to keep Titanic’s lights glowing and her power to transmit messages strong. Quite a number worked down there until almost the last minute, when there was nothing else that could be done and the engineers finally released them, and by the time many of them came up to the upper decks the lifeboats were all gone. In the wireless shack, Phillips was still working the set with Bride standing by but the power was very low. At 2.05, Capt. Smith entered the shack for the last time. ‘Men, you have done your full duty. You can do no more. Abandon your cabin, now it’s every man for himself’. Phillips continued working, sending his final wireless message at 2.10am, while Smith went round the ship releasing different groups of workers, repeating the ‘every man for himself’ mantra. Some jumped for it and managed to reach the lifeboats, others stayed on board to see what fate had in store. By the forward entrance to the grand staircase, the band, now wearing life jackets, scraped lustily away at ragtime. The calm continued for a while on the boat as people braced themselves for the drama to come. Within the ship, the heavy silence of the deserted rooms had a drama of its own. The crystal chandeliers of the a la carte restaurant hung at a crazy angle but they still burned brightly. Some of the small table lights had fallen over. The main lounge with its big fireplace was silent and empty. One passerby could hardly believe that just 4 hours earlier, the room had been filled with the most exquisitely-dressed ladies and gentlemen sipping after-dinner coffee. According to Walter Lord’s book, he smoking room was not completely empty and a steward had apparently looked in at 2.10 and found Thomas Andrews standing all alone in the room, with a stunned look on his face. Lord writes that ‘his life jacket thrown away and all his drive and energy were gone’. Andrews didn’t answer when asked if he was going to try to save himself and simply gazed at a large painting of Plymouth Harbour called ‘The Approach of The New World’, which hung above the elegant marble fireplace. However, later research found that the incident had happened prior to the steward leaving the ship at 1.30am and that Andrews had been seen on the bridge at 2.10. Out on the deck, people waited, some prayed and the band played on. Others seemed lost in thought, a mass of humanity awaiting its fate calmly and still without too much outward panic, hundreds now accumulated at the stern of the ship. They had only 10 minutes to live at this point though they wouldn’t have known that and would perhaps have retained some faith in the great ship that it would last longer than expected or even perform some kind of miracle with a hitherto unknown safety feature magically kicking in at the last minute. Reflection time was short but perhaps the ignored ice warnings would have played on Capt. Smith’s mind, the last telling them exactly where to expect the berg. Phillips could ponder the ice warning that he had replied angrily to earlier and which had never reached the bridge. At 2.10 in the wireless shack, Phillips continued to work, Bride later talking of the reverence he felt for him amid the chaos of those last 10 or 15 minutes. He and Bride knocked unconscious a stoker who’d tried to take Phillips’s life jacket, deliberately consigning him to a certain death. They’d reached several ships by now, who were steaming towards the stricken liner. Other than the Carpathia and later the Californian, it’s unclear at what point they turned back or if they reached the spot. 20 miles away, the mystery ship was seen off the port bow, agonisingly close.

When the wireless operators finally cleared out, Phillips disappeared and Bride joined the men trying to free Collapsibles A and B. It was a ridiculous place to stow boats. With the deck slanting, it was impossible to launch them but they’d decided to float them off so they toiled on, including Lightoller. Boat B was pushed to the edge of the roof and slid down on some oars to the deck, landing upside down. Boat A was a struggle as well and the men were tugging at both collapsibles when the bridge dipped under at 2.15 and the sea rolled aft along the boat deck. There was a sudden crowd of people pouring up from below who all seemed to be steerage passengers. The band were still there and at this moment the ragtime ended and the strains of a slower song, led by violinist Hartley, flowed across the deck and drifted in the still night far out over the water and within earshot of the boat. Harold Bride remembered this song as the hymn ‘Autumn’ though his testimony was later proved to be somewhat flawed in a number of respects. Most would claim that the song played at this point was ‘Nearer My God To Thee’, which would of course have had an unbearable poignancy and would become an anthem of later dramatic representations of the disaster. Down dipped the Titanic’s bow and its stern swung slowly up. As the tilt grew steeper, a wave went surging aft up the boat deck, hitting dozens of people and crashing through the dome of the forward first-class staircase, destroying the dome itself and sending huge amounts of water cascading inside it. The forward funnel toppled over, striking the water on the starboard side with a shower of sparks and a crash of tonnes of steel heard above the general uproar. It was actually a blessing to Lightoller, Bride and the others clinging to overturned Collapsible B, which was washed 30 yards clear of the plunging, twisting hull by the force of the wave and the falling funnel. Colonel Archibald Gracie rose ‘as if on the crest of a wave at the seashore’ but in the process lost his friend Clinch Smith, with whom he’d made a pact to remain together to the end, for ever. By the 4th funnel, the ship was swinging higher and higher, and a survivor heard a popping and cracking, a series of muffled thuds and the crash of glassware. The slant of the deck grew so steep that people couldn’t stand and instead slid into the water. Amid the chaos, nobody knows exactly what happened to Captain Smith except his tragic final demise. He was seen just before the end by a steward walking on to the bridge, still with his megaphone in hand. Bride saw Smith dive from the bridge into the sea and he was also seen later in the water by a fireman, holding a child. Those in the boats either watched in absolute silence or buried their heads on each other’s shoulders, unable to look. Seen and unseen, the great and the unknown tumbled together in a writhing heap as the bow plunged deeper and the stern rose higher. At 2.18am, the lights went out, flashed on again then went out for good, plunging all involved into a horrifying darkness. Not quite though as a single kerosene lantern flickered high in the after mast. The muffled thuds and tinkle of breaking glass grew louder and a steady roar, a cacophony, thundered across the water as everything not bolted down broke loose.

There has never been a mixture like it. Among the mind-boggling array of items were 29 boilers, 800 cases of shelled walnuts, 15,000 bottles of ale and stout, huge anchor chains each weighing 175 pounds, 30 cases of golf clubs and tennis rackets, tonnes and tonnes of coal, 30,000 fresh eggs, 5 grand pianos, a 50-phone switchboard, 2 reciprocating engines, a revolutionary low-pressure turbine, 8 dozen tennis balls, a cask of china for ‘Tiffany’s’, an ice-making machine and 16 beautifully-packed trunks for the wealthy Ryersons. Out in the boats, they could scarcely believe their eyes, some having watched for nearly 2 hours as the Titanic ominously sank lower and lower, hoping against hope that God or someone would save them. They saw decks and decks of people waiting, looking like bees, milling around and hoping. Survivor Ruth Becker remembered that ‘the ship looked beautiful in the dark night, the ocean like a millpond’. As the bow sank, some headed for the part of the deck not yet in the water, postponing the plunge and in fact lessening their chances by being crowded with others. 2nd Officer Lightoller instead jumped for it, later describing hitting the water, at this point 4 degrees below freezing point, as like ‘1000 knives being driven into my body’. The lifebelts were largely futile in water like this. Next was heard a different kind of sound, a tremendous booming, cracking, popping, explosive sound, which was the ship breaking in 2 between the 3rd and 4th funnels. As the bow fell, the stern settled back, and even now it may have seemed to some that the stern might hold and become its own lifeboat. Alas, it came to an even keel just briefly before rising to be perfectly perpendicular and then going down on its own. When the final plunge happened, it was the most horrifying moment of all, beauty of the night turned to a violent ugliness. There was an unearthly din, the black hull hanging at 90 degrees against a Christmas-card backdrop of brilliant stars. There was also a groan not unlike a primitive leviathan in the throes of death as the Titanic slid under, picking up speed as she went. And then she was gone. In Collapsible C, Ismay bent over his oar, unable to bear seeing her go down. Many in the boats just sat freezing cold and in a daze, showing no emotion. On The Californian, Stone and Gibson watched the ship that had fascinated them all night suddenly disappear. 20 minutes earlier at 2am, the steamer’s lights had been very low on the horizon and the 2 men felt she must be steaming away, as they then told the Captain. The sleepy Lord asked the time and for details about the rockets and rolled back over to get back to sleep. As the sea closed over the Titanic, Lady Cosmo Duff Gordon remarked to her secretary ‘there’s your beautiful nightdress gone’, a remark that you would like to think was ironic but probably wasn’t. The Titanic story was, no pun intended, a story of shallowness and depth. Later, there were tales of great heroism and humans reaching out to each other, some sacrificing themselves to save others.